Mechanics of Morphogenesis:

The Biology and Engineering Behind the Mysteries of Embryonic Development.

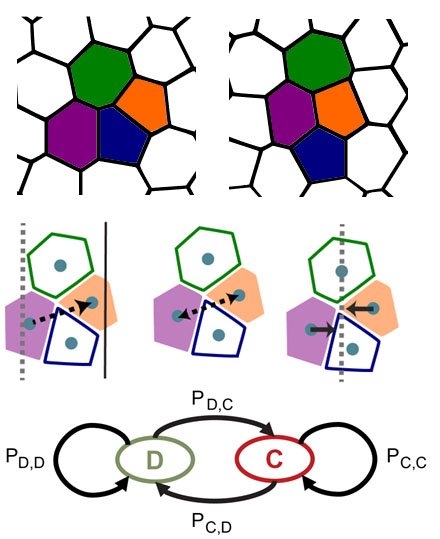

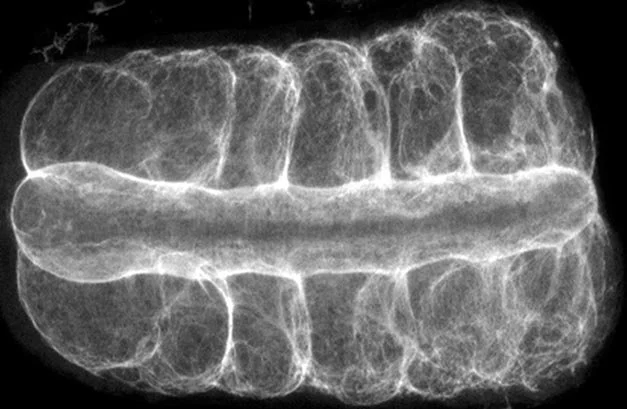

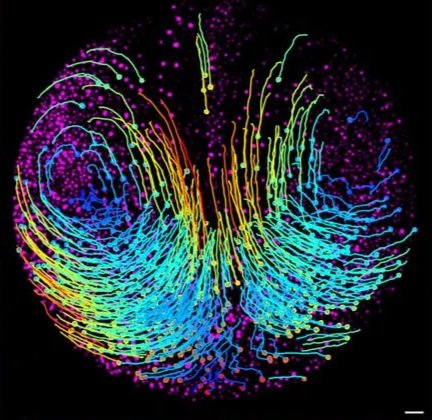

Physics Matters! Biological processes play out in the physical world where work, energy, and kinetics dictate the shape and form of embryos and organs.

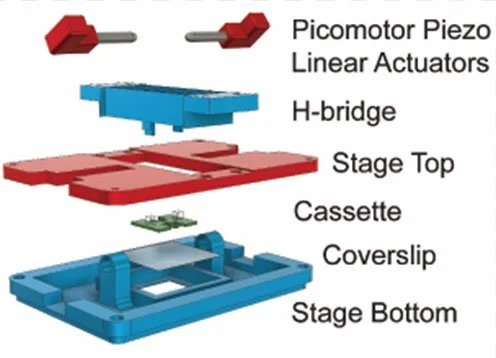

Our mission is two-fold, first, to expose the ways in which the environment, genome, cell biology, and mechanics are integrated during development, and second, to turn the principles of development into practical technologies for tissue engineering.